Abstract: In this case report, we present a compelling and illustrative account of an individual with acne who sought an alternative approach to treatment. The patient’s journey, marked by prior struggles with conventional therapies, led them to explore homeopathic remedies. The study delves into the patient’s specific symptoms, constitutional characteristics, and the personalized homeopathic regimen employed. Over the course of treatment, significant improvements in acne severity were observed, without the typical side effects associated with traditional interventions. This case report underscores the promising potential of homeopathy as a holistic and individualized method for managing acne and emphasizes the importance of further research in this area.

Keyword : Acne, Individualized treatment, Holistic approach, Dermatology, Therapeutic efficacy, Symptomatology

Introduction

Acne vulgaris, commonly known as acne, is a prevalent dermatological condition that affects individuals of various ages, but is most often associated with the adolescent years. This skin disorder is characterized by the development of a range of lesions, including blackheads, whiteheads, papules, pustules, and, in severe cases, cysts. Acne primarily manifests on the face, neck, chest, and back, areas rich in sebaceous glands.

The impact of acne extends beyond its physical manifestations, as it can significantly affect an individual’s self-esteem, mental well-being, and overall quality of life. While it is a condition that can be a source of concern and frustration, understanding its etiology, clinical presentation, and available treatment options is of paramount importance.

Acne vulgaris results from a complex interplay of factors, including increased sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, inflammation, and colonization by the bacterium Propionibacterium acnes. Hormonal fluctuations, genetic predisposition, and environmental influences also play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of this condition.(1)

Types of acne

1. Acne Vulgaris: This is the most common type of acne, characterized by whiteheads, blackheads, pustules, and papules. It typically occurs on the face, neck, chest, and back.(2)

2. Cystic Acne: Cystic acne is more severe than typical acne and results in painful, large, and often deep-seated cysts or nodules. It can lead to scarring.(3)

3. Comedonal Acne: This type of acne primarily involves comedones, which are non-inflammatory lesions. It includes both open comedones (blackheads) and closed comedones (whiteheads). (4)

4. Papulopustular Acne: Papulopustular acne is characterized by inflamed papules and pustules, which are often red and tender. It can be moderate to severe. (5)

5. Acne Conglobata: Acne conglobata is a severe and uncommon form of acne that is often associated with interconnected abscesses and widespread inflammation. It can lead to severe scarring. (6)

6. Acne Fulminans: Acne fulminans is a rare and severe form of acne that is accompanied by systemic symptoms, such as fever and joint pain. It typically affects adolescent males. (7)

7. Acne Rosacea: Acne rosacea is a chronic skin condition that primarily affects the face and is characterized by redness, flushing, and the presence of papules and pustules. (8)

8. Acne Mechanica: This type of acne is caused by friction or pressure on the skin, often due to sports equipment, helmets, or tight clothing.

Pathogenesis : The pathogenesis of acne vulgaris is a complex process involving several interconnected factors, including sebum production, follicular hyperkeratinization, inflammation, and the role of Propionibacterium acnes. Here’s a general overview about its pathogenesis.

Acne is a common skin condition that can manifest in several different types, each with its own distinct characteristics. Here are some of the most common types of acne, along with references for further reading: (9)

1. Sebum Production: Sebaceous (oil) glands in the skin produce sebum. Androgens, particularly dihydrotestosterone, play a crucial role in stimulating sebum production.(10)

2. Follicular Hyperkeratinization: In individuals with acne, the skin cells lining the hair follicles become abnormally sticky and block the follicles, leading to comedone formation. This process is partly influenced by increased production of keratin within the follicles. (11)

3. Inflammation: Inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-1α (IL-1α), contribute to inflammation in acne lesions. The release of these mediators is associated with the rupture of follicular walls and the release of sebum and follicular contents into the surrounding skin. (12)

4. Propionibacterium acnes: Propionibacterium acnes, a bacterium present on the skin, has been associated with the development of inflammatory acne. This bacterium colonizes the pilosebaceous unit and contributes to the inflammatory response. (13)

5. Genetics: Genetic factors can also play a role in acne pathogenesis. Individuals with a family history of acne may be more prone to developing the condition. (14)

6. Diet and Lifestyle: Emerging research suggests that diet and lifestyle factors, such as high glycemic index foods and dairy consumption, may influence acne development in some individuals. (15)

Case Report

A 16 year old hindu female with her mother visited the OPD of the R. B. T. S. Govt. Homoeopathic Medical College & Hospital Muzaffarpur on 15th October, 2022 with a complaint of Acne vulgaris affecting her face [Figure 1]. She was anxious and was much concerned about her skin condition. Her medical history was not remarkable. She was not taking any treatment during the first visit. There was no significant family history with her. She had taken allopathic treatment for 6 months for that problem, reportedly without any significant improvement. She had a body mass index of 21.8 .

Clinical findings

The patient had purplish eruptions on the cheeks and forehead [Figure 1], which were pointed, granular, cystic and a few pustular. There was burning, pain, and itching in the lesions with closed comedones. She was a chilly patient and had a desire for spicy food and cold drinks. Her bowels were constipated. On physical examination, comedones, papules and pustules were found.

Patient was loquacious and losing all hope of being cured. Attendant narrated about her to be jealous and consolation aggravated her symptoms.

Diagnostic assessments

After clinical findings of the patients the case was confirmed to be of acne vulgaris. Also this was a known case of acne vulgaris that had been treated conventionally by a dermatologist for 5 months. Since it was a diagnosed case, only routine investigations like a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thyroid profile, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, blood sugar and fasting serum insulin were done to rule out other disorders with acne as a common presentation.

Figure 1: (a and b) Before treatment

Therapeutic intervention

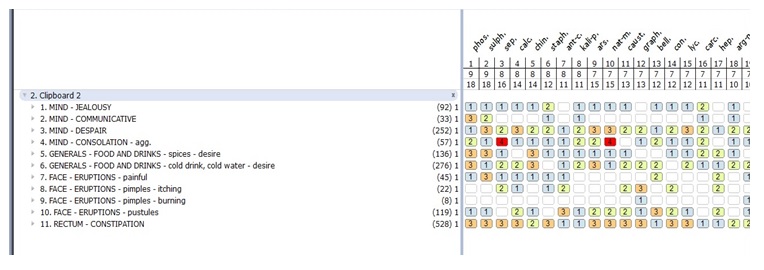

Repertorisation was done using the Synthesis repertory in Radar Opus software version 3.0.16 on the basis of 11 rubrics(16) [Figure 2]. The top four medicines were Phosphorus (18/9), Sulphur (18/9), Sepia (16/8) and Calcarea (14/8). After consulting Materia Medica,(17) Phosphorus was selected as the patient was thermally chilly and had constipation. She has a desire for spicy food and cold drinks. She had painful eruptions on face. Hence, Phosphorus 30C, 5 globules, single dose was prescribed on 15th October 2022 followed by placebo for the next 15 days. Placebo consisted of 5 globules of 30 number size, impregnated with dispensing alcohol, to be taken every morning. She was advised not to prick her acne and to avoid taking junk or fast food.

Prescription:

Single dose of phosphorus 30 C in the globules of 30 size was prescribed followed by placebo for 15 days. The patient was advised to not to touch and prick the pimples.

Follow up and outcomes

In the first follow-up, very little improvement was observed, and Placebo was prescribed for 15 days. There was still little improvement in the next follow-up on 15th Nov, 2022, After this prescription, there was a slight improvement in pain, burning and itching, but new acne continued to appear. There was no further improvement in the skin condition [Figure 4]. However, in next visit, 01/12/2022 the characteristic finding of purple discoloration of the lesion was focussed upon and a high dose of Phosphorus was prescribed. Eventually, sustained improvement followed. The modified Naranjo criteria(18) used for assessing causal attribution of improvement yielded a total score of 9 [Table 2]. The Cardiff Acne Disability Index also reduced from 15 to 2 after the treatment [Table 3].

On subsequent follow-ups, there was continuous improvement based on the clinical assessment, as shown in Table 3. At the end of the treatment, there was remission of acne [Figure 3], and the quality of life was improved after treatment [Table 4].

Fig. 2: Repertorisation chart

Discussion

The case report presented here sheds light on the potential of homeopathic remedy phosphorus in the management of Acne vulgaris, a common dermatological condition. It can have a profound impact on a patient’s quality of life. Acne vulgaris presents a challenge for healthcare providers, and while conventional treatments exist, they may not be universally effective and can often be associated with adverse effects. The exploration of alternative therapies such as homeopathy, is vital to meet the diverse needs of patients. In this case, Sulphur, a frequently used homeopathic remedy, was chosen due to its historical use in various skin conditions, including Acne vulgaris. The remedy was prescribed following a meticulous assessment of the patient’s individual symptomatology, constitution, and unique presentation of acne.

Figure 3 (a and b) : After treatment

In this instance, the Acne vulgaris vanished along with general improvements in the physical and mental domains.

| Table 1: Treatment history | ||

| Date | Symptoms | Medicine with doses and repetition |

| 15/10/2022 29/10/2022 15/11/2022 01/12/2022 19/12/2022 05/01/2023 21/01/2023 | Itchy and burning pustules on forehead and cheeks. Itching slightly reduced, the appearance of acne same. Pustules same. Few new acne developed, which were nodular and cystic in appearance. Purple discolouration of eruptions found, itching and burning reduced remarkably. Better, No new acne Better, face almost clear. No new eruptions Facial and mental symptoms were recovered | Phosphorus 30, 5 globules and placebo for 15 days Placebo for 15 days Placebo for 15 days Phosphorus 200, 5 globules and placebo for 15 days Placebo for 15 days Placebo for 15 days Placebo for 15 days |

There MONARCH scores were examined to evaluate the clinical advancement brought on by the suggested intervention. It demonstrates that clinical progress is not a result of regression to the mean or a natural process. The MONARCH score demonstrates that homoeopathic treatment was the only factor in the chance of improvement.

| Table 2: Modified Naranjo Criteria | |||

| Domains | Yes | No | Not sure |

| 1. Was there an improvement in the main symptom or condition for which the homeopathic medicine was prescribed? | +2 | ||

| 2. Did the clinical improvement occur within a plausible timeframe relative to the drug intake? | +1 | ||

| 3. Was there an initial aggravation of symptoms? | +1 | ||

| 4. Did the effect encompass more than the main symptom or condition (i.e., were other symptoms ultimately improved or changed)? | +1 | ||

| 5. Did overall well-being improve? (suggest using validated scale) | +1 | ||

| 6A Direction of cure: did some symptoms improve in the opposite order of the development of symptoms of the disease? | 0 | ||

| 6B Direction of cure: did at least two of the following aspects apply to the order of improvement of symptoms: –from organs of more importance to those of less importance? –from deeper to more superficial aspects of the individual? –from the top downwards? | 0 | ||

| 7. Did “old symptoms” (defined as non-seasonal and non-cyclical symptoms that were previously thought to have resolved) reappear temporarily during the course of improvement? | 0 | ||

| 8. Are there alternate causes (other than the medicine) that—with a high probability—could have caused the improvement? (Consider known course of disease, other forms of treatment, and other clinically relevant interventions) | +1 | ||

| 9. Was the health improvement confirmed by any objective evidence? (e.g., laboratory test, clinical observation, etc.) | +2 | ||

| 10. Did repeat dosing, if conducted, create similar clinical improvement? | 0 | ||

| Total score : +9 | |||

Table 3: The Cardiff Acne Disability Index (At the beginning of treatment)

| 1. As a result of having acne, during the last month have you been aggressive, frustrated or embarrassed? | ? | Very much indeed (3)A lot (2)A little (1)Not at all (0) |

| 2. Do you think that having acne during the last month interfered with your daily social life, social events or intimate personal relationships? | ? | Severely, affecting all activities (3)Moderately, in most activities (2)Occasionally or in only some activities (1)Not at all (0) |

| 3. During the last month have you avoided public changing facilities or wearing swimming costumes because of your acne? | ? | All of the time (3)Most of the time (2)Occasionally (1)Not at all (0) |

| 4. How would you describe your feelings about the appearance of your skin over the last month? | ? | Very depressed and miserable (3)Usually concerned (2)Occasionally concerned (1)Not bothered (0) |

| 5. Please indicate how bad you think your acne is now: | ? | The worst it could possibly be (3)A major problem (2)A minor problem (1) Not a problem (0) |

| Total Score : 15/15 | ||

Table 4: The Cardiff Acne Disability Index (At the end of treatment)

| 1. As a result of having acne, during the last month have you been aggressive, frustrated or embarrassed? | ? | Very much indeed (3)A lot (2)A little (1)Not at all (0) |

| 2. Do you think that having acne during the last month interfered with your daily social life, social events or intimate personal relationships? | ? | Severely, affecting all activities (3)Moderately, in most activities (2)Occasionally or in some activities (1)Not at all (0) |

| 3. During the last month have you avoided public changing facilities or wearing swimming costumes because of your acne? | ? | All of the time (3)Most of the time (2)Occasionally (1)Not at all (0) |

| 4. How would you describe your feelings about the appearance of your skin over the last month? | ? | Very depressed and miserable (3)Usually concerned (2)Occasionally concerned (1)Not bothered (0) |

| 5. Please indicate how bad you think your acne is now: | ? | The worst it could possibly be (3)A major problem (2)A minor problem (1) Not a problem (0) |

| Total Score : 2/15 | ||

Conclusion

The case report that is being given shows how specific homoeopathic treatment can successfully cure Acne vulgaris and enhance quality of life. To demonstrate the position of homoeopathy as one of the trustworthy therapy options available to patients for such a severe type of acne, well-designed clinical studies will be necessary. Homoeopathy has a great scope to cure the Acne vulgaris because of its Holistic concept.

References

- Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. In: Griffiths CEM, Barker J, Bleiker T, Chalmers R, Creamer D, editors. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 9th ed. Wiley; 2016.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Acne. In: Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2015.

- Harper JC. Cystic acne: A review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(8):897-902.

- Thiboutot D. Comedone formation: etiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(5):367-374.

- Leyden JJ, Preston N, Osborn C, Gottschalk RW. A single-center, randomized double-blind, parallel group study to examine the safety and efficacy of 3 mg drospirenone/0.02 mg ethinyl estradiol compared with placebo in the treatment of moderate truncal acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(6):590-595

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973

- Marzano AV, Borghi A, Cugno M, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum and acne conglobata: An extensive review and a comprehensive proposal of a therapeutic option. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45(2):203-214

- Powell FC. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):793-803

- Bojar RA, Cunliffe WJ, Holland KT. The short-term treatment of acne vulgaris with benzoyl peroxide: effects on the surface and follicular cutaneous microflora. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(2):204-208

- Leyden JJ, et al. 1998. The role of sebaceous glands in acne pathogenesis: Clinical and therapeutic implications. Dermatology, 196(1): 19-21.)

- Katsambas AD, et al. 2010. Acne: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Clinics in Dermatology, 28(2): 111-118.)

- Thiboutot D, et al. 2009. Pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: Recent advances. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 58(5): S2-S5

- Webster GF. 1995. Inflammation in acne vulgaris. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 33(2): 247-253

- Bataille V, et al. 2002. A twin study of acne. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 119(3): 701-705

- Burris J, et al. 2021. Diet and Acne: A Review of the Evidence. Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications, 11(3): 96-105

- Schroyens F. Radar Opus Software 3.0.16. Synthesis Treasure Edition. Zeus Soft; 2009

- Boericke W. Pocket Manual of Homoeopathic Materia Medica & Repertory: Comprising of the Characteristic and Guiding Symptoms of All Remedies (clinical and Pahtogenetic [sic]) Including Indian Drugs. B. Jain publishers; 2002.

- Lamba CD, Gupta VK, van Haselen R, Rutten L, Mahajan N, MollaAM, et al. Evaluation of the modified Naranjo criteria for assessing causal attribution of clinical outcome to homeopathic intervention as presented in case reports. Homeopathy 2020;109:191-7.

About the author

- Dr Nishant Kumar, PG Scholar, RBTS Govt. Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital Muzaffarpur, Bihar

- Dr Sarita Kumari, PG Scholar, RBTS Govt. Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital Muzaffarpur, Bihar

- Dr Deepak kumar, PG Scholar, RBTS Govt. Homoeopathic Medical College and Hospital Muzaffarpur, Bihar